I watched HAIL CAESAR, the most recent theatrical film by the Coen Brothers, again last night, this time on my 100" screen in my basement theater. It's a movie that I fell in love with instantly the first time I saw it, even though it took me a second viewing to really get adjusted to just

why I loved it so much.

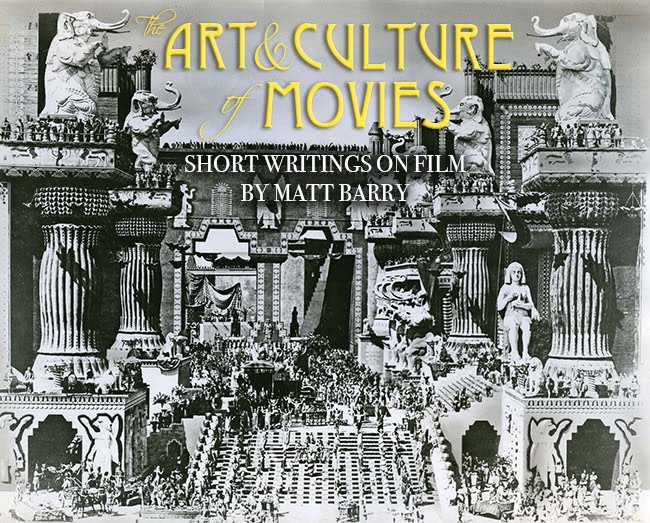

Released to mixed critical reviews and frequently negative audience response, HAIL CAESAR is, to me, one of the very best of all of the Coen brothers' films, a loving tribute to the magic of movies. The episodic plot follows a day in the life of a harried studio executive, brilliantly played by Josh Brolin, as he struggles to bring to completion the studio's big Biblical epic "Hail Caesar", after its star (George Clooney) has been kidnapped and held for ransom by a group calling itself "The Future", all the while dealing with his stable of eccentric stars and their various personal problems in order to maintain equilibrium behind the scenes of his Dream Factory.

More than most films dealing with the movie industry, HAIL CAESAR explores the religious aspect that movies can play in our lives, and the power that they have to shape our dreams and our vision of ourselves. The film is set in the early 1950s at that moment just when the seams were really beginning to show at the edges of the Movie Capital of the World, and directors like Billy Wilder were beginning to explore the seamy side of Tinseltown in films like SUNSET BLVD. This image of a Hollywood gone to seed has been mined before in films like LA CONFIDENTIAL, HOLLYWOODLAND and even Tim Burton's ED WOOD, but the Coens approach it with a deft combination of lightness and grandeur that beautifully contrasts the tangled web of behind-the-scenes goings-on at the studio, and the projected illusion of fantasy that we continue to believe in.

The brilliance here lies in the fact that the Coens convey this magic through the use of movie archetypes in the characters in situations, and by structuring the film around the production of a biblical epic about an arrogant Roman officer who is blinded by faith after encountering the face of Jesus. By extending the religious metaphor to the power of film itself, the Coens create one of the medium's most insightful commentaries on itself.