Monday, December 25, 2017

The Shop Around the Corner (1940)

Sunday, December 03, 2017

Cabaret (1972)

Given his background in theater, it is remarkable just how cinematic Bob Fosse's directorial efforts in film were. Indeed, he began directing films at a time when the musical genre had largely become passe, ossified by over-produced, stiff and lifeless works that were a far cry from the glory days of the genre a couple decades prior.

Enter Fosse and Cabaret (1972), which re-defined the genre and breathed real vitality and verve into the musical film. What is remarkable about Fosse's direction is how he uses the camera and editing as another part of his choreography -- not through cute or clever gimmicks but rather by integrating them so completely that they are all really of a piece. His style is at once electric and explosive, and yet, somehow, never calls attention to itself in a way that makes anything seem out of place. The performance of Liza Minnelli is central to the film's style, her physicality so perfectly in-tune with Fosse's visual approach that their collaboration achieves a kind of synergy.

Cabaret follows the relationship between Sally Bowles (Liza Minnelli), an American cabaret singer in Weimar-era Berlin, and British student Brian Roberts (Michael York), who is in Berlin as part of his doctoral research. The cabaret itself, the Kit Kat Klub, serves as a kind of communal spot in a city that is beginning to become overrun with Nazis, whose rise to power parallels the events in the lives of Sally and Brian over the course of the film.

Although based on the hit Broadway show of the same name, for his film Fosse returned to the original source material (The Berlin Stories by Christopher Isherwood) for inspiration, and songwriters John Kander and Fred Ebb jettisoned all but one of the tunes from their Broadway score, and wrote new songs for the film. The result is a remarkably rich, poignant, and stylish film that has lost none of its power.

Saturday, December 02, 2017

Iron Man (1931)

Tod Browning is so closely associated today with the macabre and often gruesome thrillers for which he achieved his greatest fame (Dracula, Freaks, The Unknown) that it is easy to forget that he worked in a number of different genres. One example is Iron Man (1931), a pre-Code boxing melodrama that was one of three films he made for Universal in the early '30s, sandwiched in between his loose 1930 remake of his 1921 crime drama Outside the Law, and his iconic horror film Dracula.

Tod Browning is so closely associated today with the macabre and often gruesome thrillers for which he achieved his greatest fame (Dracula, Freaks, The Unknown) that it is easy to forget that he worked in a number of different genres. One example is Iron Man (1931), a pre-Code boxing melodrama that was one of three films he made for Universal in the early '30s, sandwiched in between his loose 1930 remake of his 1921 crime drama Outside the Law, and his iconic horror film Dracula.Iron Man stars Lew Ayres (one year after his star-making performance in All Quiet on the Western Front) as a young prizefighter who bounces back after losing his first fight, but once he achieves some success, his gold-digging wife (Jean Harlow) re-appears in his life, and after convincing him to dump his long-time manager (Robert Armstrong), the boxer's career begins to fall apart.

Browning had a knack for this kind of hard-hitting, gritty, urban material, as evidenced here and in Fast Workers (1933), which makes one curious to see what he would have done had he been able to explore it more frequently in the pre-Code sound film period.

Friday, December 01, 2017

"Le Squelette Joyeux" (1897) -- A Lumiere Trick Film

This is an interesting subject from Louis and Auguste Lumiere, of the kind of subject matter one does not typically associate with them.

It would appear to have been inspired by the early trick films of Melies, whose HAUNTED CASTLE of the previous year features a skeleton (although it doesn't dance). Or it could be a case of the Lumieres borrowing from similar theatrical traditions to branch out into new avenues of filmmaking.

Either way, it's an intriguing little subject. What I find most interesting about it is how, despite its fantastic nature, it actually appears quite drab and plain compared to the strikingly rich photographic compositions of the Lumiere actualities, which breathe with life and vitality.

I wonder which of their cameramen shot this subject, and if he ever did anything else similar to it?

It would appear to have been inspired by the early trick films of Melies, whose HAUNTED CASTLE of the previous year features a skeleton (although it doesn't dance). Or it could be a case of the Lumieres borrowing from similar theatrical traditions to branch out into new avenues of filmmaking.

Either way, it's an intriguing little subject. What I find most interesting about it is how, despite its fantastic nature, it actually appears quite drab and plain compared to the strikingly rich photographic compositions of the Lumiere actualities, which breathe with life and vitality.

I wonder which of their cameramen shot this subject, and if he ever did anything else similar to it?

Wednesday, November 29, 2017

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939)

There was an anecdote I read years ago -- and I've forgotten where I read it now -- about a joke circulating in Hollywood during World War II, something to the effect of "In the case of an air raid, go over to RKO Radio Pictures -- they haven't had a hit in years."

That always puzzled me, because it seems to me that RKO produced many of the finest individual films of the studio era. Of course, it's possible that this did not translate to big box office hits that some of the other studios may have enjoyed, but the quality of the studio's output speaks for itself with such fine films as Citizen Kane, King Kong, Gunga Din, Bringing Up Baby, Little Women, and the Astaire-Rogers cycle, among many others.

Chief among the examples of RKO's great films must be the 1939 production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, starring Charles Laughton in the title role. His achingly beautiful performance stands as one of his finest accomplishments in a long career filled with memorable roles. It has been noted that the Hunchback has relatively little screen time for what is the starring role, and yet Laughton's presence looms large over the film. Even when he is off-screen, we never forget about him. Laughton is one of many fine actors in a cast that includes Maureen O'Hara (in her first Hollywood film), Sir Cedric Hardwicke, Thomas Mitchell, and a youthful Edmond O'Brien, among others.

What really stands about the film is its exceptional production values. I have read that, at the time, Hunchback was the second-most expensive production RKO had yet undertaken (the most expensive being Gunga Din, released the same year), and it shows. Medieval Paris is brought to life in great scale on the RKO backlot, aided by impressive matte paintings. William Dieterle, one of the more interesting studio craftsmen working in Hollywood's studio system, and frequent John Ford cinematographer Joseph H. August create a vivid atmosphere that brims with bustling activity in the daylight, and a sense of quiet menace in the shadow of night.

Perhaps because it was released in that remarkable year of 1939, The Hunchback of Notre Dame has been overshadowed somewhat by the other great films of that year, and does not seem to be revived as often as some of those other films (not just the perennial favorites Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz, but also the genre-defining Stagecoach and the Capra classic Mr. Smith Goes to Washington). But it stands as the equal of any of the other great films of 1939, and remains one of the finest achievements of the Hollywood studio system.

That always puzzled me, because it seems to me that RKO produced many of the finest individual films of the studio era. Of course, it's possible that this did not translate to big box office hits that some of the other studios may have enjoyed, but the quality of the studio's output speaks for itself with such fine films as Citizen Kane, King Kong, Gunga Din, Bringing Up Baby, Little Women, and the Astaire-Rogers cycle, among many others.

Chief among the examples of RKO's great films must be the 1939 production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, starring Charles Laughton in the title role. His achingly beautiful performance stands as one of his finest accomplishments in a long career filled with memorable roles. It has been noted that the Hunchback has relatively little screen time for what is the starring role, and yet Laughton's presence looms large over the film. Even when he is off-screen, we never forget about him. Laughton is one of many fine actors in a cast that includes Maureen O'Hara (in her first Hollywood film), Sir Cedric Hardwicke, Thomas Mitchell, and a youthful Edmond O'Brien, among others.

What really stands about the film is its exceptional production values. I have read that, at the time, Hunchback was the second-most expensive production RKO had yet undertaken (the most expensive being Gunga Din, released the same year), and it shows. Medieval Paris is brought to life in great scale on the RKO backlot, aided by impressive matte paintings. William Dieterle, one of the more interesting studio craftsmen working in Hollywood's studio system, and frequent John Ford cinematographer Joseph H. August create a vivid atmosphere that brims with bustling activity in the daylight, and a sense of quiet menace in the shadow of night.

Perhaps because it was released in that remarkable year of 1939, The Hunchback of Notre Dame has been overshadowed somewhat by the other great films of that year, and does not seem to be revived as often as some of those other films (not just the perennial favorites Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz, but also the genre-defining Stagecoach and the Capra classic Mr. Smith Goes to Washington). But it stands as the equal of any of the other great films of 1939, and remains one of the finest achievements of the Hollywood studio system.

Saturday, November 25, 2017

Justus D. Barnes: Early Film Star

Justus D. Barnes (1862-1946), who achieved immortality on film as the bandit who fires his gun into the camera at the end of THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY. He came to films from the stage, and worked for both the Edison and Thanhouser companies. He retired from acting in 1917 and later worked as a milkman and ran a cigar store.

Wednesday, November 22, 2017

Laurel & Hardy in "The Devil's Brother" (1933)

The first of Laurel and Hardy's operetta films, and quite possibly the best, adapted from the 1830 show by Daniel Auber. The boys play down-on-their-luck vagabonds in 18th century Italy who reluctantly become the bumbling assistants to the notorious bandit chief Fra Diavolo ("The Devil's Brother"). Comedy highlights include Laurel's "kneesy-earsy-nosey" finger games and Laurel becoming intoxicated while filling bottles in a wine cellar. The soundtrack retains a number of the songs from Auber's original score. Singer Dennis King brings the perfect mix of menace and charm to the title role, supported by a fine cast including Thelma Todd as the bored noblewoman, James Finlayson as her cuckold husband, and Henry Armetta as the long-suffering innkeeper whose inability to imitate Laurel's "finger games" causes him no end of frustration. One of the only Laurel and Hardy films directed by their long-time producer Hal Roach.

Sunday, November 19, 2017

Sturges and Slapstick

Watching THE LADY EVE again, I was struck by something about Preston Sturges' technique that I've written about before here. I always hedge about coming out with this outright criticism of his otherwise marvelous films, but after having recently seen both LADY EVE and UNFAITHFULLY YOURS, those films have re-enforced my opinion that Sturges simply never mastered the kind of slapstick comedy of which he was so fond of inserting into his films, and that, contrasted with the smooth flow of his dialogue, the slapstick moments stand out for their awkwardness.

The major slapstick moments in THE LADY EVE occur during the part in which Fonda is re-introduced to Stanwyck posing as another woman. He is so distracted by her resemblance to the con-woman he fell in love with on his ocean cruise back from South America that he is continually tripping over himself. Fonda, never a slapstick performer, handles the business admirably, but it feels labored and stiff, not helped by the undercranking to underscore the comic effect. Only his third bit of slapstick in this sequence -- when he brings his head up on a tea tray -- provokes the kind of surprised laughter that the best slapstick earns. It is that element of surprise, created from building up the gags, that Sturges seems to struggle to find in these moments.

In a previous post on SULLIVAN'S TRAVELS, I'd written that Sturges never seemed to be able to solve the problem of finding a way to get his characters to fall into a swimming pool. As Joel McCrea and Veronica Lake argue, she threatens to push him into the pool, and in the rather chaotic ensuing struggle between McCrea, Lake and the butler, all tumble into the pool. When Sullivan's valet attempts to pull the butler out of the pool, he is himself pulled in, at which point the scene ends. It's funny enough, but feels chaotic and hurried.

That is something I have come to admire all the more about Sturges' contemporaries in film comedy, especially Leo McCarey, George Stevens and Frank Capra, all of whom had come up in silent comedy and understood slapstick staging and timing inside out. These men knew how to make the slapstick sequences organic to the whole and of a piece, whereas in Sturges' films, these scenes stick out and call attention to themselves.

As a contrast with how Sturges handles the pool scene in SULLIVAN, I would point to the famous scene in Capra's IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE, with the floor of the high school gym opening up to reveal a swimming pool in the middle of the Charleston contest. As Stewart and Reed dance deliriously, blissfully unaware of the potential embarrassment that awaits them, we watch in anticipation of the big moment when they will fall in. It's a cathartic moment they finally do, and is only heightened by the other students diving in. The flustered school principal, watching nervously from the sidelines, finally decides that it looks like so much fun that he dives in, too -- a nice capper to the sequence. A scene like this could easily be out of place and distracting in a film like IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE, but Capra draws on his slapstick training to make it entirely of a piece.

As a final point of contrast, I would point to a scene from another Sturges film I had recently seen, UNFAITHFULLY YOURS. This is one of Sturges' most brilliantly conceived and executed comedies, almost like a symphony in its intricate construction. But there is a lengthy and protracted slapstick sequence with Rex Harrison, involving his efforts to retrieve his dictation machine from a top shelf, which brings the proceedings to a halt. Sturges lets this scene play out for minutes on end, and while it was clearly intended to be a comic exercise in frustration à la W.C. Fields, it is instead just frustrating in its failure to build to anything.

I offer this only as an example of how Sturges' contemporaries, who had spent years working in silent comedy for producers like Mack Sennett and Hal Roach, were able to keep the slapstick tradition alive in their films 20 years on. Sturges was unmatched at creating unique comic worlds, populated with his favorite character actors speaking that wonderful concoction of Sturges dialogue that is his hallmark. But when it comes to slapstick, I continue to believe that Sturges never quite mastered finding a way to integrate it into his world of comedy.

The major slapstick moments in THE LADY EVE occur during the part in which Fonda is re-introduced to Stanwyck posing as another woman. He is so distracted by her resemblance to the con-woman he fell in love with on his ocean cruise back from South America that he is continually tripping over himself. Fonda, never a slapstick performer, handles the business admirably, but it feels labored and stiff, not helped by the undercranking to underscore the comic effect. Only his third bit of slapstick in this sequence -- when he brings his head up on a tea tray -- provokes the kind of surprised laughter that the best slapstick earns. It is that element of surprise, created from building up the gags, that Sturges seems to struggle to find in these moments.

In a previous post on SULLIVAN'S TRAVELS, I'd written that Sturges never seemed to be able to solve the problem of finding a way to get his characters to fall into a swimming pool. As Joel McCrea and Veronica Lake argue, she threatens to push him into the pool, and in the rather chaotic ensuing struggle between McCrea, Lake and the butler, all tumble into the pool. When Sullivan's valet attempts to pull the butler out of the pool, he is himself pulled in, at which point the scene ends. It's funny enough, but feels chaotic and hurried.

That is something I have come to admire all the more about Sturges' contemporaries in film comedy, especially Leo McCarey, George Stevens and Frank Capra, all of whom had come up in silent comedy and understood slapstick staging and timing inside out. These men knew how to make the slapstick sequences organic to the whole and of a piece, whereas in Sturges' films, these scenes stick out and call attention to themselves.

As a contrast with how Sturges handles the pool scene in SULLIVAN, I would point to the famous scene in Capra's IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE, with the floor of the high school gym opening up to reveal a swimming pool in the middle of the Charleston contest. As Stewart and Reed dance deliriously, blissfully unaware of the potential embarrassment that awaits them, we watch in anticipation of the big moment when they will fall in. It's a cathartic moment they finally do, and is only heightened by the other students diving in. The flustered school principal, watching nervously from the sidelines, finally decides that it looks like so much fun that he dives in, too -- a nice capper to the sequence. A scene like this could easily be out of place and distracting in a film like IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE, but Capra draws on his slapstick training to make it entirely of a piece.

As a final point of contrast, I would point to a scene from another Sturges film I had recently seen, UNFAITHFULLY YOURS. This is one of Sturges' most brilliantly conceived and executed comedies, almost like a symphony in its intricate construction. But there is a lengthy and protracted slapstick sequence with Rex Harrison, involving his efforts to retrieve his dictation machine from a top shelf, which brings the proceedings to a halt. Sturges lets this scene play out for minutes on end, and while it was clearly intended to be a comic exercise in frustration à la W.C. Fields, it is instead just frustrating in its failure to build to anything.

I offer this only as an example of how Sturges' contemporaries, who had spent years working in silent comedy for producers like Mack Sennett and Hal Roach, were able to keep the slapstick tradition alive in their films 20 years on. Sturges was unmatched at creating unique comic worlds, populated with his favorite character actors speaking that wonderful concoction of Sturges dialogue that is his hallmark. But when it comes to slapstick, I continue to believe that Sturges never quite mastered finding a way to integrate it into his world of comedy.

Wednesday, November 15, 2017

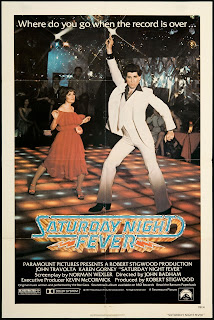

"Saturday Night Fever" (1977) Director's Cut

It's an interesting contradiction that a film that is so very much of a specific time and place (late '70s Brooklyn, at the height of the Disco craze) has held up so well for 40 years. It's one of those films that, I imagine, must have seemed hopelessly dated in one sense just a few years after its release. But perhaps now, separated by the distance of time, we can better appreciate its strengths and qualities that keep audiences coming back to it.

The story of Tony Manero, a young working-class Italian-American man in Brooklyn struggling to find himself through the only thing that matters to him -- dancing -- is certainly one audiences continue to identify with. John Travolta's star-making performance, John Badham's energetic direction and the pulsating music of the Bee Gees elevate the film to an experience that still brims with vitality. Norman Wexler's script (based on "Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night", an article by Nik Cohn that appeared in New York Magazine the previous year) is startlingly honest, granting real seriousness to Tony's struggle to move beyond the world he knows and make a name for himself.

After seeing SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER on the big screen, I was struck by just what a nicely-photographed film it is. I think this gets lost when watching the film on TV, or even on DVD, where some of the definition and detail is lost, but there are some moments that are really quite stunning. The cinematographer, Ralf D. Bode, frequently shoots the closeups of Travolta and Karen Lynn Gorney together with a soft, gauzy look that gives them a dreamlike quality, which contrasts effectively with the naturalism of the scenes with Travolta and his friends. He brings a similar quality to the dance sequences (particularly the "Night Fever" number), heightened by the colorful flashing lights and fog on the dance floor. Looking over his filmography, I realize I have only seen a couple other films photographed by Bode, but I do not remember anything particularly unique about their cinematography. In any case, he did really fine work on SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER, which is greatly emphasized by seeing the film on a big screen.

Further Reading:

"Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night" by Nik Cohn

Roger Ebert's 1977 Review of Saturday Night Fever

Roger Ebert's "Great Movies" review of Saturday Night Fever

Janet Maslin's Review of Saturday Night Fever in the New York Times (Dec. 16, 1977)

"Saturday Night Fever at 40: You Should Still Be Dancing"

The story of Tony Manero, a young working-class Italian-American man in Brooklyn struggling to find himself through the only thing that matters to him -- dancing -- is certainly one audiences continue to identify with. John Travolta's star-making performance, John Badham's energetic direction and the pulsating music of the Bee Gees elevate the film to an experience that still brims with vitality. Norman Wexler's script (based on "Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night", an article by Nik Cohn that appeared in New York Magazine the previous year) is startlingly honest, granting real seriousness to Tony's struggle to move beyond the world he knows and make a name for himself.

After seeing SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER on the big screen, I was struck by just what a nicely-photographed film it is. I think this gets lost when watching the film on TV, or even on DVD, where some of the definition and detail is lost, but there are some moments that are really quite stunning. The cinematographer, Ralf D. Bode, frequently shoots the closeups of Travolta and Karen Lynn Gorney together with a soft, gauzy look that gives them a dreamlike quality, which contrasts effectively with the naturalism of the scenes with Travolta and his friends. He brings a similar quality to the dance sequences (particularly the "Night Fever" number), heightened by the colorful flashing lights and fog on the dance floor. Looking over his filmography, I realize I have only seen a couple other films photographed by Bode, but I do not remember anything particularly unique about their cinematography. In any case, he did really fine work on SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER, which is greatly emphasized by seeing the film on a big screen.

Further Reading:

"Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night" by Nik Cohn

Roger Ebert's 1977 Review of Saturday Night Fever

Roger Ebert's "Great Movies" review of Saturday Night Fever

Janet Maslin's Review of Saturday Night Fever in the New York Times (Dec. 16, 1977)

"Saturday Night Fever at 40: You Should Still Be Dancing"

Monday, November 13, 2017

"The Movie"

Something that has stuck with me, ever since I first read Roger Ebert's review of CASABLANCA, was his description of it as "The Movie". I knew exactly what he meant by that, and still agree with the assessment. Although I prefer to avoid such hyperbole as "greatest", "best", "most important" and other such ultimately meaningless platitudes in talking about films, there is something about CASABLANCA that has elevated it to a level of enduring cultural iconic status that is, I think, perhaps unique.

It was especially fun seeing the film on the big screen in a state-of-the-art megaplex (the Towson Cinemark theater). We went for the 2pm show but it was already sold out, so we got tickets for 7pm and it played to a packed house. Some of the Bogart cult was in attendance, complete with trenchcoats and fedoras, reciting the iconic lines.

Especially in this day and age, when the moviegoing experience seems to be split between bigger, louder, and emptier Hollywood fare, and the museum-like reverence of the art and revival house, it can be a breath of fresh air to view a classic like CASABLANCA as a living, breathing, vital experience, as fresh today as it was 75 years ago.

Saturday, November 11, 2017

Movie Soundtracks & Frame Blow-up Books

There was also a series of books, many by Richard J. Anobile, that served a similar purpose and included frame blow-ups and dialogue transcriptions from famous films. I have one called Why a Duck?, which consists of scenes from the Marx Bros.' comedies. Anobile wrote others, too, including Who's on First, A Flask of Fields, A Fine Mess, plus individuals volumes on classics such as PSYCHO, THE MALTESE FALCON and FRANKENSTEIN, among others. He even wrote one on THE GENERAL, though it's hard to imagine how his scene-by-scene frame blowups would work for a silent film.

I wonder how many people still collect these? Home video eventually rendered these kinds of books and albums obsolete, but as classic film comedy fans know, it's hard to ever pass up a chance to spend time with your favorite comedians, no matter what the format.

Friday, November 10, 2017

Unexpected Audience Laughter

I noticed something interesting at last night's SUSPIRIA screening -- though it was hard to miss, as it was actually quite distracting: sometime around the second half of the film, roughly half the audience began laughing raucously at the film, which totally took me right out of the carefully-crafted, haunting atmosphere of the experience.

It reminded me of my experiences watching VERTIGO, another haunting, dream-like film that often inspires fits of uncomfortable laughter from audiences. At least in that case I can understand the laughter as a nervous response to the increasingly unhinged behavior of the Jimmy Stewart character.

I'll never forget the first time I saw VERTIGO with an audience in film school years ago. There was one moment in particular that got such a strong laugh from everyone in the room but me, and I've never understood it. It occurs when Scottie Ferguson gives the distraught Judy Barton a brandy and tells her to drink it down. That moment got a huge laugh from everyone. The professor, also laughing, said, "Hey, it was the '50s..."

I still didn't get it.

There was another incident I recall, more recently, during a screening of ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT at Loew's Jersey City. At the moment of the reveal that Kropp's leg has been amputated, someone in the audience let out a loud burst of uncomfortable laughter, possibly out of surprise. The poor devil was the only person in the entire house to react that way, so it must have been embarrassing.

At least it was an honest reaction.

Monday, November 06, 2017

Hitchcock's Perfection

Taking in a screening of Hitchcock's THE 39 STEPS recently, I realized that this has become probably my most oft-watched Hitchcock film. Certainly it's the one I can return most frequently without losing any of the suspense or freshness of Hitchcock's technique. As I wrote in a recent post on NORTH BY NORTHWEST, sometimes the iconic sequences of Hitchcock's best-known films can come to play better in my mind, where they exist in a kind of rosy retrospection.

That is not the case with THE 39 STEPS, however. It is a film I have seen probably at least a half-dozen times if not more, and each time I am swept up anew in the breathless pace of the endlessly engaging story, the erotic chemistry of Robert Donat and Madeleine Carroll's performances, and of course, Hitchcock's masterful technique that shows his fertile creative mind at its most active and visionary. After the screening, I commented that the film is one of the very few that I would describe as "perfect" -- not a wasted frame or extraneous moment in the entire piece.

I find, more and more, that I am drawn to the early works of directors, often those formative films made before they hit their full stride and became identified with a certain style or genre. I'm not sure if I would consider THE 39 STEPS to be an "early" Hitchcock film, given that it was already something like his 20th film as a director, and made fifteen years after he'd entered the film industry. But it nonetheless contains the kind of energy and vitality and creative experimentation that I associate with the earlier films of directors, and in terms of Hitchcock's filmography, it certainly set the standard for many of his most successful films to follow, not to mention establishing a prototype for the entire espionage film genre.

Sunday, November 05, 2017

"Rosemary's Baby" and Great Character Actors

ROSEMARY'S BABY must have one of the finest casts of character actors since some of the classic Universal horror films of the '30s and '40s. Made by Paramount in 1968, the film straddles the very tail end of the last vestiges of the old studio system, and the era of New Hollywood. And one of the best aspects of the former is the great roster of character actors who make up much of the supporting cast.

Watching the film again at the Charles Theatre recently, right before Halloween, I raced to count all the familiar names in the opening credits: in addition to the wonderful Ruth Gordon, we have Sidney Blackmer, Maurice Evans, Ralph Bellamy, Patsy Kelly, and Elisha Cook Jr., among others. Seeing these familiar faces as characters involved in a Satanic cult makes the proceedings all the more unsettling. Polanski likely chose these actors precisely for their strong identification with certain "types", which would have been especially recognizable to moviegoers in 1968. It's an inspired casting decision.

And I love seeing John Cassavetes do his impression of Elisha Cook!

Monterey Pop and the Avant Garde

I watched D.A. Pennebaker's film of MONTEREY POP a few weeks ago at the Senator Theatre in Baltimore for the first time, and hadn't jotted down any thoughts on it yet, perhaps because it is such an "experience" beyond being just a filmed record of the concert.

However, something that I have found myself thinking about quite a bit since then is the way that the film, and indeed, much of the Direct Cinema movement, fuses the concepts and energies of both the documentary and avant garde traditions. There are sequences in MONTEREY POP show the direct influence (and directly influenced?) the techniques of Jonas Mekas' diary film shooting style, for example.

Similarly, if you look at an earlier film by Pennebaker, DAYBREAK EXPRESS (1953), it's difficult to even classify -- is it a documentary of a morning train commute, or an avant garde city symphony (or jazz riff, in this case), animated in light and shadow? Why can't it be both?

Labels:

Avant Garde,

D.A. Pennebaker,

Documentary,

Monterey Pop

The Blair Witch Project & Low Budget Filmmaking

In retrospect, I've wondered if it was the success of BLAIR WITCH PROJECT that really kicked off the period of excitement for low-budget DIY filmmaking in the early 2000s? Certainly the early success stories of Robert Rodriguez and Kevin Smith paved the way for this kind of thing, but even in the '90s, there was still considerable cost involved if shooting on 16mm or 35mm. That BLAIR WITCH (shot on 16mm and Hi8 video) coincided with the availability of consumer-level digital tools made filmmaking seem open to anyone with a good idea, and the possibilities endless.

I wonder if there is a film since then that has had the same kind of impact on aspiring filmmakers?

Saturday, November 04, 2017

North by Northwest (1959)

I caught a screening of this Hitchcock classic as part of the Filmtalk screening and discussion series at the Enoch Pratt Library this afternoon. I hadn't seen it in several years, at least. Despite its status as perhaps the "ultimate" Hitchcock film, I have to confess it is not one that I re-watch as frequently as some of his other movies, even though it is undoubtedly an immensely enjoyable film. This isn't so much due to overexposure, as I have not actually seen it that many times compared to, say, PSYCHO, or THE 39 STEPS, or even ROPE. For some reason, it's a film that has tended to play better in my mind, perhaps due to the standout sequences (the crop-duster, Mount Rushmore) that rank among some of the most iconic in all of cinema.

So it came as a pleasant surprise, upon seeing it again for probably the first time in at least a decade, that I enjoyed this highly entertaining film even more than expected. More than ever lately, I have found how much more I enjoy seeing films with an audience, even if just a few people, where you can share in the experience of the film together.

As I mentioned above, NORTH BY NORTHWEST is a film that holds few surprises for me at this point, even if I do hold a good deal of affection for it. This time around I was struck more than ever by the playfulness of Hitchcock's approach, and even moments of wry humor, such as the strains of "It's a Most Unusual Day" wafting through the hotel lobby moments before Cary Grant is kidnapped. And I was struck by Hitchcock's unconventional (especially for the period) use of space and time in building up to the crop-dusting sequence. The lengthy stretches of silence and the vast expanse of the landscape in the moments leading up to the attack by the plane look forward to his use of similar elements, to an even greater degree, in THE BIRDS a few years later.

And was there ever a director with more of a gift for making actors look good than Hitchcock? NORTH BY NORTHWEST offers strong evidence that the answer is "no".

So it came as a pleasant surprise, upon seeing it again for probably the first time in at least a decade, that I enjoyed this highly entertaining film even more than expected. More than ever lately, I have found how much more I enjoy seeing films with an audience, even if just a few people, where you can share in the experience of the film together.

As I mentioned above, NORTH BY NORTHWEST is a film that holds few surprises for me at this point, even if I do hold a good deal of affection for it. This time around I was struck more than ever by the playfulness of Hitchcock's approach, and even moments of wry humor, such as the strains of "It's a Most Unusual Day" wafting through the hotel lobby moments before Cary Grant is kidnapped. And I was struck by Hitchcock's unconventional (especially for the period) use of space and time in building up to the crop-dusting sequence. The lengthy stretches of silence and the vast expanse of the landscape in the moments leading up to the attack by the plane look forward to his use of similar elements, to an even greater degree, in THE BIRDS a few years later.

And was there ever a director with more of a gift for making actors look good than Hitchcock? NORTH BY NORTHWEST offers strong evidence that the answer is "no".

Tuesday, October 31, 2017

Thomas H. Ince: American Cinema Pioneer

|

| American cinema pioneer Thomas H. Ince (1880-1924) |

In 1912, Ince built a massive studio, named "Inceville", which was the first all-purpose film studio built in Hollywood; and in 1915, he partnered with D.W. Griffith and Mack Sennett to form the Triangle Motion Picture Company, one of the first studios to handle both production and distribution (the studio itself was located at the current site of Sony Pictures). Later on, Ince was briefly involved with Adolph Zukor in the formation of Paramount, but desired to return to working independently.

By the early 1920s, Ince was no longer quite the heavy hitter in Hollywood that he'd been a decade earlier. His life came to an abrupt and tragic end in 1924, while aboard the yacht of William Randolph Hearst, under circumstances that remain unclear to this day, due to conflicting reports from all involved. Likely due to his untimely death, and the fact that he was not easily identified with key landmark films of the silent era in the way that Griffith, DeMille, and certain other directors were, Ince's legacy tended to fade from film history, but he made a tremendous impact on the Western genre, on the development of the American film industry, and on the studio system model that would make Hollywood the center of that industry.

Friday, October 06, 2017

Dinner at Eight (1933)

Wonderful, sharply-written ensemble comedy-drama following the individual stories of different characters attending a high-society dinner party, which interweave to create an alternately witty and funny, solemn and even tragic tapestry of the human condition.

Directed by George Cukor. Screenplay by Frances Marion and Herman J. Mankiewicz, from the play by George S. Kaufman and Edna Ferber, with additional dialogue by Donald Ogden Stewart. Starring Marie Dressler, John Barrymore, Wallace Beery, Jean Harlow, Lionel Barrymore, Lee Tracy, Edmund Lowe and Billie Burke. Exquisitely photographed by William Daniels.

Thursday, October 05, 2017

Merrily We Go To Hell (1932)

Pre-code melodrama about an alcoholic writer -- played by Fredric March -- and his disastrous marriage to Sylvia Sidney that leads to tragedy but ultimately redemption. March delivers a fine performance that prefigures his performance as Norman Maine in A STAR IS BORN five years later. Directed by Dorothy Arzner.

Friday, September 01, 2017

TWO GIANTS OF FILM COMEDY

Mack Sennett and Buster Keaton on the set of "Hollywood Cavalcade" (1939). For this tale of the early days of Hollywood starring Don Ameche and Alice Faye, Sennett supervised the silent film sequences featuring Buster Keaton, and which were directed by Mal St. Clair, who'd co-directed two of Keaton's silent shorts. Ironically, Keaton was one of the few major silent clowns who never actually worked for Sennett during the silent era.

Tuesday, August 29, 2017

Robert Mitchum in "Cape Fear" (1962)

Watching CAPE FEAR again last night for the first time in years, I was struck by the highly effective sense of dreamlike frustration in the climactic sequence on board the houseboat, with Peck's helpless frustration as he watches the boat get cut loose and float away, frantically swimming after it, and then learning that it was all a distraction while Mitchum has already made his way back to shore to attack Peck's teenage daughter.

I couldn't help comparing Mitchum's terrifying performance here with his characterization in NIGHT OF THE HUNTER. The difference is that CAPE FEAR takes a realistic approach, firmly rooted in the conventions of its genre and in the classical style, where NIGHT OF THE HUNTER is like a dream and stands own its own as something totally unique.

I've become fascinated by Mitchum recently -- an absolutely fearless actor with a seemingly intuitive sense of how to play each role he undertook...versatile doesn't begin to describe his range.

Wednesday, July 26, 2017

Tales of Manhattan (1942)

I watched this film the other night. It's one of those omnibus films like IF I HAD A MILLION or O. HENRY'S FULL HOUSE -- with five stories involving a cursed tailcoat as it is transferred from one owner to the next and changes their fortunes in the process -- except this one is the work of a single director, Julien Duvivier, which accounts for the stylistic consistency between the individual segments here when compared with other films of this kind.

The five segments are all interesting if rather offbeat stories acted by major stars including Charles Boyer, Rita Hayworth, Henry Fonda, Ginger Rogers, Charles Laughton, Edward G. Robinson, Paul Robeson and Ethel Waters, among many others. (the copy I saw is missing the W.C. Fields sequence that was restored in the '90s, which is often cited as a highlight and which I've seen elsewhere, but is far from being among The Great Man's best work).

It's too bad Hollywood doesn't make films like this anymore, outside of the odd example such as 1989's NEW YORK STORIES or 2008's NEW YORK, I LOVE YOU. The format offers a lot of potential to tell short stories and the best of them can operate like variations on a theme.

A side note, but there's a particular little moment in this film that I loved: Eugene Pallette delivers the tailcoat to Henry Fonda's manservant Roland Young, who is cleaning up balloons and other debris after a wild party the night before. Young lets go of the balloons, which float up to the ceiling. A moment later, one balloon bursts off-screen, presumably from coming into contact with the hot klieg lights at the top of the set, and the men react to it briefly, while continuing on with their dialogue. Likely it was all done in a single take and was left in. It's the kind of little moment that reminds you you're watching a movie, and it calls attention to the all the hardware just out of camera range above the actors on the soundstage.

Tuesday, July 25, 2017

Film Prints with Stories to Tell

Something I often find interesting in the older, pre-restoration versions of silent films that long circulated on 16mm are the listings of the archival sources through which the prints were acquired, or the program notes and the original year of release added on to the beginning of the film when they were shown as part of a larger program or series. I've seen a number of these older editions used as sources for public domain videotapes and DVD releases over the years, which I like to think of as carrying on the life of these prints...almost as if they have their own stories to tell.

Monday, July 24, 2017

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

Great big-screen showing of THE MALTESE FALCON at the Charles tonight. The model of Classical Hollywood economic storytelling. It's a film that cries out to be seen on the big screen -- you become aware of the subtle but masterful technique Huston uses to keep things visually interesting even through pages of dialogue. Great performances all around -- everyone makes an impression and makes the most of their roles, especially Greenstreet, who comes in somewhat late in the picture but commands attention in every scene in which he appears. It's a watershed Hollywood film in some ways -- helping to usher in the era of the writer-director in the early '40s, and pushing the hardboiled detective genre film into new territory, with Spade's torn conscience about turning in the woman he has fallen for while remaining bound by honor and duty to his partner whom she killed. Spade's sarcastic kidding about Brigid O'Shaughnessy's compulsive lying masks an uncertainty and even insecurity about his feelings for her and whether she can be trusted, whether she will ultimately hurt him. His shield of cynicism toward her at the end betrays his vulnerability. A brilliant and even beautiful film...mysterious, evocative...the stuff that dreams are made of.

Labels:

Film Reviews,

Humphrey Bogart,

John Huston,

The Maltese Falcon

Tuesday, July 18, 2017

Unfaithfully Yours (1948)

Preston Sturges' final classic was this farce comedy about a temperamental symphony conductor (Rex Harrison) who suspects his wife (Linda Darnell) has been unfaithful to him, and his overheated imagination gets the better of him as he concocts various schemes to exact revenge on his wife and her supposed lover.

An interesting blend of Sturges' characteristic comedy-of-manners laced with slapstick, and a strong dose of dark comedy, UNFAITHFULLY YOURS is an uneven but highly interesting and often quite funny film. It is filled with Sturges' sharp observations about human behavior, offering a wry commentary on how the best laid plans often go awry.

Friday, July 14, 2017

German Buster Keaton

One of the great curiosities of the early sound film period are the foreign-language versions of Hollywood films made for overseas markets. Long unseen in the US, many of these were shot simultaneously, often with a different director and supporting cast, on the same sets as the domestic version. These multi-lingual versions were produced to fill the void left by the demise of Hollywood silent films that were highly popular in foreign markets.

Keaton's struggles at MGM are well-documented, but they are worth reiterating here when one

Keaton's struggles at MGM are well-documented, but they are worth reiterating here when one

considers that not only was he forced to make these films not just once, but often multiple times, each in different languages. Following a non-speaking appearance in MGM's THE HOLLYWOOD REVUE OF 1929, a variety-show style film in which most of the studio's major talent performed musical numbers and sketches to show off their voices, Keaton appeared in the musical comedy FREE AND EASY (1930), in which he was required to sing and dance as well as engage in uncharacteristically labored verbal humor. To top it off, the film was simultaneously shot in a Spanish-language version titled ESTRELLADOS.

Subsequent foreign-language versions of Keaton's early MGM talkies include De Frente, Marchen (a Spanish version of DOUGHBOYS [1930]), Buster se Marie and Casanova wider Willen (French and German versions, respectively, of PARLOR, BEDROOM AND BATH [1931]), and Le plombier amoureux (a French version of THE PASSIONATE PLUMBER [1932]). The advent of dubbing and subtitling helped bring an end to the practice of shooting separate foreign-language versions of Hollywood films around 1932.

Distinctive from the other foreign-language versions that Keaton appeared in, however, is WIR SCHALTEN UM AUF HOLLYWOOD (1931, We Switch to Hollywood, a reference to the radio broadcast report from Hollywood that serves as the set-up for the movie). Sometimes described as a German-language version of THE HOLLYWOOD REVUE OF 1929, WIR SCHALTEN UM AUF HOLLYWOOD is instead an entirely unique film. This is where WIR SCHALTEN UM AUF HOLLYWOOD differs from the typical foreign-language version of the period, rather than simply re-creating the domestic version shot-for-shot but in a different language.

The main draw of THE HOLLYWOOD REVUE OF 1929 was in being able to hear many of MGM's biggest stars talk on-screen for the first time. But WIR SCHALTEN UM AUF HOLLYWOOD was released a full two years later, in 1931, by which time these same stars had already been talking on the screen for quite a while, so the novelty of hearing their voices had presumably worn off. Whereas HOLLYWOOD REVUE was a standard variety-style presentation of the studio's top talent, similar to Warners' SHOW OF SHOWS or PARAMOUNT ON PARADE, WIR SCHALTEN UM AUF HOLLYWOOD takes an entirely different approach.

Subtitled "Eine reportage revue" ("a reportage revue"), the premise finds a German reporter (played by Austrian cabaret performer Paul Morgan) coming to Hollywood with a wireless hand-held radio transmitter to give audiences back home a report of his experiences in Tinseltown. He arrives at MGM, and meets a deposed German nobleman, now working as an extra at the studio, and together, the two tour the lot, interviewing stars along the way and culminating with attending a red carpet movie premiere. Sprinkled throughout are musical numbers lifted from THE HOLLYWOOD REVUE OF 1929, as well as the unfinished 1930 musical revue THE MARCH OF TIME (sequences shot for this never-completed production were used in a number of MGM films of the period, and the All Talking! All Singing! All Dancing! blog features a thorough history of the production and a breakdown of its recycled music numbers)

Directed by German actor Frank Reicher (best remembered by audiences today as the Skipper in KING KONG), the cast includes the famous Austrian cabaret star Paul Morgan (who also wrote the screenplay and dialogue), Buster Keaton (who receives second billing among the all-star cast, an indicator of his box office clout abroad at the time), Ramon Novarro, Nora Gregor, Oscar Straus, Adolphe Menjou, Heinrich George, the Dodge Sisters, John Gilbert, Egon von Jordan, and the Albertina Rasch Ballet. Uncredited appearances include Wallace Beery, Joan Crawford, Gustav Froehlich, Hoot Gibson, Anita Page, Dita Parlo, Norma Shearer and, perhaps most unexpectedly, Russian filmmaker Sergei M. Eisenstein (who was in Hollywood at the time).

Also worth noting is that the film was photographed by special effects cameraman Ray Binger (though the cinematography throughout is visually unremarkable), and is the earliest known film to have been edited by Adrienne Fazan, who would become one of MGM's most highly-valued and long-time cutters, working on such productions as SINGIN' IN THE RAIN, AN AMERICAN IN PARIS, and SOME CAME RUNNING, among many others.

Buster Keaton appears in two scenes in the film, totaling just under five minutes of screentime. In the first, he is spotted in a restaurant by Paul Morgan, who tries to interview him, but Buster is unresponsive to him (with the exception of borrowing the wireless radio transmitter to crack some walnuts). Buster only shows attention when he spots a pretty waitress, and follows her out of the restaurant. At this point he is able to engage in some characteristic physical humor. He is first seen reclining in a doorframe, holding himself up by pressing his feet on the opposite side of the frame (re-creating a pose he had used in a publicity still for his 1922 short THE ELECTRIC HOUSE). Next, he steps out of the doorway, which we now see is quite high off the ground, and onto the roof of his car underneath. He nonchalantly jumps off the roof of his car, gets in, and tools off, much to the amusement of Morgan and his companion. Keaton's appearance here is almost completely nonverbal, with only a single line spoken in German.

Keaton's second scene occurs at the very end of the film. Following the movie premiere, Paul Morgan sends his farewell address over the radio. Buster emerges from an alley next to the theater, dressed in caveman attire and carrying a club, which he uses to knock Morgan over the head before delivering the film's final line (in stilted German) at the fade-out. His random appearance (and costume) here suggest that perhaps he appeared at another point in the film, but that it was cut. Some filmographies state that Keaton appeared as a caveman in THE MARCH OF TIME (Marion Meade in Cut to the Chase says he "had two days shooting as a caveman"), which could explain the costume here. It is possible that his footage from that earlier film could have originally been included here, but later cut, or does not survive in extant prints of the film. These two scenes give Keaton an opportunity to perform material entirely different from his scenes in THE HOLLYWOOD REVUE OF 1929.

Although it serves a similar purpose as THE HOLLYWOOD REVUE OF 1929 in giving audiences glimpses of some of MGM's biggest stars, it is inaccurate to describe WIR SCHALTEN UM AUF HOLLYWOOD as merely a German-language version of that earlier film. It is instead an entirely original creation. It is of interest to film historians today not just as an example of a unique early Hollywood foreign-language talkie, but also for the personalities it showcases, its behind-the-scenes glimpses of the MGM studio, and its inclusion of scenes from the unfinished MARCH OF TIME. It is also of great historical value as a filmed record of Paul Morgan, one of the most celebrated cabaret stars of Weimar-era Berlin before his arrest and subsequent tragic and brutal death in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in 1938 at the hands of the Nazis.

And, as valuable filmed records go, it gives us a chance to see fresh Keaton material, however minimal, which is always a welcome and wonderful thing.

Examples include a German-language version of ANNA CHRISTIE (1930), directed by Jacques Feyder and starring Greta Garbo and Salka Viertel; a German-language MOBY DICK (1930), directed by Michael Curtiz and William Dieterle (who also replaced John Barrymore as the star); and perhaps most famously, the Spanish-language version of DRACULA (1931), directed by George Melford and starring Carlos Villarias, which some critics consider to be superior to the Bela Lugosi version for its comparatively fluid camera movement.

Especially popular in foreign markets were the comedians. Hal Roach produced foreign-language versions of short comedies starring Laurel and Hardy, Charley Chase and Our Gang, often with the stars reading their lines phonetically off a blackboard. In the case of Laurel and Hardy, who enjoyed great popularity in Spain and South America, the team not only made Spanish-language versions of their two-reel comedies, they were even sometimes expanded to four or five reels in length (often by combining the plots of two or more shorts) in order to market them as features and charge higher rental fees in those markets. These foreign language versions are thus not simply carbon copies of the domestic version, but often differ significantly.

At MGM, Buster Keaton -- the studio's star comedian in the early days of sound -- was struggling to adapt not only to the new medium of sound film, but the constraints imposed on him by the corporate hierarchy of the studio system. Accustomed to the creative freedom that he'd enjoyed working for Joseph M. Schenck during the 1920s, Keaton found himself increasingly reined in after his expensive comedy epic THE GENERAL under-performed at the box office in 1927, and the subsequent combined factors of his signing with MGM and the end of the silent film form in which he had perfected his art marked a massive change in his working methods and the kind of comedies that he could make.

Keaton's struggles at MGM are well-documented, but they are worth reiterating here when one

Keaton's struggles at MGM are well-documented, but they are worth reiterating here when one considers that not only was he forced to make these films not just once, but often multiple times, each in different languages. Following a non-speaking appearance in MGM's THE HOLLYWOOD REVUE OF 1929, a variety-show style film in which most of the studio's major talent performed musical numbers and sketches to show off their voices, Keaton appeared in the musical comedy FREE AND EASY (1930), in which he was required to sing and dance as well as engage in uncharacteristically labored verbal humor. To top it off, the film was simultaneously shot in a Spanish-language version titled ESTRELLADOS.

Subsequent foreign-language versions of Keaton's early MGM talkies include De Frente, Marchen (a Spanish version of DOUGHBOYS [1930]), Buster se Marie and Casanova wider Willen (French and German versions, respectively, of PARLOR, BEDROOM AND BATH [1931]), and Le plombier amoureux (a French version of THE PASSIONATE PLUMBER [1932]). The advent of dubbing and subtitling helped bring an end to the practice of shooting separate foreign-language versions of Hollywood films around 1932.

Distinctive from the other foreign-language versions that Keaton appeared in, however, is WIR SCHALTEN UM AUF HOLLYWOOD (1931, We Switch to Hollywood, a reference to the radio broadcast report from Hollywood that serves as the set-up for the movie). Sometimes described as a German-language version of THE HOLLYWOOD REVUE OF 1929, WIR SCHALTEN UM AUF HOLLYWOOD is instead an entirely unique film. This is where WIR SCHALTEN UM AUF HOLLYWOOD differs from the typical foreign-language version of the period, rather than simply re-creating the domestic version shot-for-shot but in a different language.

The main draw of THE HOLLYWOOD REVUE OF 1929 was in being able to hear many of MGM's biggest stars talk on-screen for the first time. But WIR SCHALTEN UM AUF HOLLYWOOD was released a full two years later, in 1931, by which time these same stars had already been talking on the screen for quite a while, so the novelty of hearing their voices had presumably worn off. Whereas HOLLYWOOD REVUE was a standard variety-style presentation of the studio's top talent, similar to Warners' SHOW OF SHOWS or PARAMOUNT ON PARADE, WIR SCHALTEN UM AUF HOLLYWOOD takes an entirely different approach.

|

| Paul Morgan in 1906 |

Directed by German actor Frank Reicher (best remembered by audiences today as the Skipper in KING KONG), the cast includes the famous Austrian cabaret star Paul Morgan (who also wrote the screenplay and dialogue), Buster Keaton (who receives second billing among the all-star cast, an indicator of his box office clout abroad at the time), Ramon Novarro, Nora Gregor, Oscar Straus, Adolphe Menjou, Heinrich George, the Dodge Sisters, John Gilbert, Egon von Jordan, and the Albertina Rasch Ballet. Uncredited appearances include Wallace Beery, Joan Crawford, Gustav Froehlich, Hoot Gibson, Anita Page, Dita Parlo, Norma Shearer and, perhaps most unexpectedly, Russian filmmaker Sergei M. Eisenstein (who was in Hollywood at the time).

Also worth noting is that the film was photographed by special effects cameraman Ray Binger (though the cinematography throughout is visually unremarkable), and is the earliest known film to have been edited by Adrienne Fazan, who would become one of MGM's most highly-valued and long-time cutters, working on such productions as SINGIN' IN THE RAIN, AN AMERICAN IN PARIS, and SOME CAME RUNNING, among many others.

Buster Keaton appears in two scenes in the film, totaling just under five minutes of screentime. In the first, he is spotted in a restaurant by Paul Morgan, who tries to interview him, but Buster is unresponsive to him (with the exception of borrowing the wireless radio transmitter to crack some walnuts). Buster only shows attention when he spots a pretty waitress, and follows her out of the restaurant. At this point he is able to engage in some characteristic physical humor. He is first seen reclining in a doorframe, holding himself up by pressing his feet on the opposite side of the frame (re-creating a pose he had used in a publicity still for his 1922 short THE ELECTRIC HOUSE). Next, he steps out of the doorway, which we now see is quite high off the ground, and onto the roof of his car underneath. He nonchalantly jumps off the roof of his car, gets in, and tools off, much to the amusement of Morgan and his companion. Keaton's appearance here is almost completely nonverbal, with only a single line spoken in German.

Keaton's second scene occurs at the very end of the film. Following the movie premiere, Paul Morgan sends his farewell address over the radio. Buster emerges from an alley next to the theater, dressed in caveman attire and carrying a club, which he uses to knock Morgan over the head before delivering the film's final line (in stilted German) at the fade-out. His random appearance (and costume) here suggest that perhaps he appeared at another point in the film, but that it was cut. Some filmographies state that Keaton appeared as a caveman in THE MARCH OF TIME (Marion Meade in Cut to the Chase says he "had two days shooting as a caveman"), which could explain the costume here. It is possible that his footage from that earlier film could have originally been included here, but later cut, or does not survive in extant prints of the film. These two scenes give Keaton an opportunity to perform material entirely different from his scenes in THE HOLLYWOOD REVUE OF 1929.

Although it serves a similar purpose as THE HOLLYWOOD REVUE OF 1929 in giving audiences glimpses of some of MGM's biggest stars, it is inaccurate to describe WIR SCHALTEN UM AUF HOLLYWOOD as merely a German-language version of that earlier film. It is instead an entirely original creation. It is of interest to film historians today not just as an example of a unique early Hollywood foreign-language talkie, but also for the personalities it showcases, its behind-the-scenes glimpses of the MGM studio, and its inclusion of scenes from the unfinished MARCH OF TIME. It is also of great historical value as a filmed record of Paul Morgan, one of the most celebrated cabaret stars of Weimar-era Berlin before his arrest and subsequent tragic and brutal death in the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in 1938 at the hands of the Nazis.

And, as valuable filmed records go, it gives us a chance to see fresh Keaton material, however minimal, which is always a welcome and wonderful thing.

Sunday, July 09, 2017

Shoot the Piano Player (1960)

One of Truffaut's lightest (and most enjoyable) films, a clever homage to Hollywood crime films. A brilliant concert pianist (Charles Aznavour) who has fallen on hard times and is playing in a small-time club runs afoul of a pair of gangsters who are after his brother, while pursuing a romance with the club's waitress (Marie Dubois). Truffaut deftly creates a film that works both as a crime thriller on its own and as a playful riff on the genre at the same time, expertly balancing suspense and comedy from one moment to the next, enlivened by the director's stylistic flourishes, especially his use of cutaways.

Labels:

Film Reviews,

Francois Truffaut,

French New Wave

Friday, June 09, 2017

Round About Hollywood (1931)

This 1931 travelogue of Hollywood is notable for having been shot in the Cinecolor process, providing rare color glimpses of the Movie Capital in the early '30s. Highlights include nighttime footage from the premiere of Frank Capra's Dirigible at Grauman's Chinese Theater, aerial views of the Hollywood Bowl, and the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce building. Perhaps due to time and budgetary constraints (the film was made by the British company Wardour Films), the travelogue refreshingly offers fewer views of the iconic sights of Hollywood typically found in these types of scenic films, instead presenting quotidian views of the town's houses, streets and churches that serve as a valuable cinematic time capsule.

Friday, June 02, 2017

Murmur of the Heart (1971)

MURMUR OF THE HEART (1971, dir. Louis Malle) -- Finally got around to seeing this controversial but powerful coming-of-age story about a precocious middle class boy in 1950s France. His burgeoning adolescent escapades are cut short by a heart murmur, and he is sent off to a sanatorium with his mother, where things take a much darker and unexpected turn. Sensitively directed by Louis Malle (whose films I always find worthwhile), I was struck by the honesty in his handling of the material, especially in the film's painful and shocking climactic scene. The film's low-key energy is enhanced by an excellent jazz score featuring Charlie Parker, Henri Renaud, and Gaston Frèche. Starring Lea Massari, Benoît Ferreux, and Daniel Gélin; written and directed by Louis Malle.

Wednesday, May 24, 2017

Bonnie Scotland (1935)

Laurel and Hardy come to Scotland to collect an inheritance and through a series of misunderstandings find themselves enlisted in the Scottish regiment of the British Army and sent off to India. This one contains at least three classic scenes: Hardy's sneezing fit at the bottom of a lake that leaves it completely dry, the Boys cooking a fish in their hotel room ("it shrizzled"), and their dancing to "The Hundred Pipers" while sweeping up trash, much to the ire of Sergeant James Finlayson.

Labels:

Bonnie Scotland,

Film Comedy,

Film Reviews,

Laurel and Hardy

Sunday, May 14, 2017

Eraserhead (1977)

Last night, I saw that the newly-renovated and re-opened Parkway Film Center in Baltimore was going to be showing David Lynch's Eraserhead, a film I have never seen all the way through. I had previously begun watching it when it was available on Netflix or one of the various streaming platforms, but found that the small-screen format made it difficult to immerse myself in the alternate universe that Lynch creates.

Seeing it on the big screen, in a new 4K digital restoration, sounded more like the proper way to experience this film, which has such a devoted following that I have to confess I wondered if it would be able to live up the hype I've heard surrounding it for so long.

I arrived at the Parkway just in time for the 9:45 show on Saturday night, which these days is about as close to a "midnight movie" screening as you're going to find in the area. I purchased my ticket at the counter, and took my seat inside Theater 1, the largest of the three theaters at the Parkway.

Finally seeing Eraserhead, I can understand its appeal to those looking for something different, for viewers interested in alternative possibilities for narrative cinema. Lynch creates a surreal hallucination following a night in the life of a young man who experiences a strange series of events after being left to tend after his newborn "baby", filled with nightmarish imagery, and a surprising number of moments of real humor. It fits well with the kind of uncanny cinematic universe that Lynch has created in other films, though it is perhaps less even, less consistent than his mature films. Here, the moments of self-conscious "strangeness" stand out a little too sharply. But Lynch still conjures up a real sense of dread and unease, masterfully demonstrating early on the hallmarks of his mature cinematic style.

I am glad that I finally saw Eraserhead, and under good conditions, because it really is a unique and highly original film that retains its power even after inspiring many imitations, and it's still exciting to see the movie that heralded David Lynch as a major new filmmaking force at the time of its release.

Seeing it on the big screen, in a new 4K digital restoration, sounded more like the proper way to experience this film, which has such a devoted following that I have to confess I wondered if it would be able to live up the hype I've heard surrounding it for so long.

I arrived at the Parkway just in time for the 9:45 show on Saturday night, which these days is about as close to a "midnight movie" screening as you're going to find in the area. I purchased my ticket at the counter, and took my seat inside Theater 1, the largest of the three theaters at the Parkway.

Finally seeing Eraserhead, I can understand its appeal to those looking for something different, for viewers interested in alternative possibilities for narrative cinema. Lynch creates a surreal hallucination following a night in the life of a young man who experiences a strange series of events after being left to tend after his newborn "baby", filled with nightmarish imagery, and a surprising number of moments of real humor. It fits well with the kind of uncanny cinematic universe that Lynch has created in other films, though it is perhaps less even, less consistent than his mature films. Here, the moments of self-conscious "strangeness" stand out a little too sharply. But Lynch still conjures up a real sense of dread and unease, masterfully demonstrating early on the hallmarks of his mature cinematic style.

I am glad that I finally saw Eraserhead, and under good conditions, because it really is a unique and highly original film that retains its power even after inspiring many imitations, and it's still exciting to see the movie that heralded David Lynch as a major new filmmaking force at the time of its release.

Friday, April 14, 2017

Fatal Attraction (1987)

Friday, March 31, 2017

Louis Lumiere (1968)

Too often, the films of Louis Lumiere and other early cinema pioneers are discussed as primitive artifacts, a kind of cinematic equivalent of cave paintings that marked the beginning of an art form. This documentary, directed by Eric Rohmer, takes a formal approach, discussing the photographic qualities of the Lumiere films through interviews with Jean Renoir and Henri Langlois. Both men offer eloquent commentary on the beauty and historical value of the Lumiere films, revealing why these pioneering works should be viewed as sophisticated, fully realized motion pictures on their own terms, rather than as merely a precursor of things to come.

Labels:

Eric Rohmer,

Henri Langlois.,

Jean Renoir,

Louis Lumiere

Martin Scorsese and Edwin S. Porter

Watching The King of Comedy (1983) last night, I remembered reading that Scorsese had been influenced by Edwin S. Porter's Life of an American Fireman (1903) in thinking about his approach to making the film. I watched it partly with that in mind, thinking about how he might have drawn on that film for inspiration. One of the things I find most interesting about Scorsese is how he ingests the whole of film history and brings those influences to bear in such unexpected but effective ways.

This is what Scorsese had to say about the influence of Porter's film on The King of Comedy:

"People had reacted in such a way to Raging Bull, saying it was a beautiful film - like Days of Heaven, you could take every frame and put it on the wall - that I decided my next picture was going to be 1903 style, more like Edwin S Porter's The Life of an American Fireman, with no close-ups. So in King of Comedy that's what I tried to do." (quoted in Scorsese on Scorsese).

Friday, March 24, 2017

Submarine Patrol (1938)

A minor John Ford film, especially in relation to his classics Stagecoach and Young Mr. Lincoln that he would make the following year. It's a lightweight adventure yarn about a ragtag group of sailors on a Navy sub chaser during WWI. Richard Greene and Preston Foster head up a fine ensemble cast that includes Nancy Kelly, George Bancroft, Slim Summerville, John Carradine, Elisha Cook Jr., and Henry Armetta, among others.

Ford's direction keeps the pace energetic and lively throughout, embellished with a characteristic sense of humor. There are some exciting action sequences, such as the sea battle and sinking of a German sub, which are impressively staged and heightened by excellent model work, especially in the undersea shots.

This is the kind of material John Ford could do so well, and though he would return to the settings and themes again, this seems to mark a turning point in his career. The light, freewheeling tone places it among his earlier work, specifically among his other Navy films like Salute (1929), Men Without Women (1930), and Seas Beneath (1931), rather than the films he would make during and after the war.

Ford's direction keeps the pace energetic and lively throughout, embellished with a characteristic sense of humor. There are some exciting action sequences, such as the sea battle and sinking of a German sub, which are impressively staged and heightened by excellent model work, especially in the undersea shots.

This is the kind of material John Ford could do so well, and though he would return to the settings and themes again, this seems to mark a turning point in his career. The light, freewheeling tone places it among his earlier work, specifically among his other Navy films like Salute (1929), Men Without Women (1930), and Seas Beneath (1931), rather than the films he would make during and after the war.

Thursday, March 23, 2017

Patterns (1956)

A powerful and at times excruciating drama -- written by Rod Serling from his own teleplay -- about the cutthroat office politics inside a big New York industrial firm, where the tension runs so thick one could cut it with a knife. Van Heflin plays a brilliant young executive from the company's Ohio office, who accepts a top position in New York, but soon finds himself being used as a pawn in a power play by the big boss (Everett Sloane) to force a principled, aging executive (Ed Begley) into resigning.

Directed by Fielder Cook with stark minimalism, and filmed on location in New York (in striking black and white by Boris Kaufman), Serling's screenplay boils with tension and anxiety, only occasionally becoming too self-conscious, and impaired by an ending that doesn't ring entirely true, but that does not negate the astonishing degree of honesty and poignancy that Serling establishes leading up to it.

Thursday, March 16, 2017

Swiss Miss (1938)

In to a small town high in the Alps, riding in a mule-drawn sleigh, arrive Laurel and Hardy. This time they are mousetrap salesmen, and have come to Switzerland because, according to Laurel's logical thinking, where there is more cheese than anywhere else in the world, there will be more mice. Like two comic vagabonds, the boys are seemingly as much at home in this fantasy version of a Tyrolean village as they are in the old west or the suburbs of Los Angeles, a testament to their universality and timelessness. During their stay in Switzerland, Oliver Hardy will endure the usual trials and tribulations against his dignity, most of them innocently precipitated upon him by his friend, Stan Laurel.

From the moment they appear, you find it impossible to take your eyes off of them. The boys' masterful comic interplay, which they make look so deceptively simple, astounds with its perfect rhythm and timing, every gesture, every glance and every pratfall performed with expert precision. Every facet of their screen characters is so thoroughly and richly defined to the point where they seem so real, so human that we feel like we are spending time with old friends when we see their films.

Numerous episodes stand out for their comic ingenuity. Spotting a Saint Bernard with a keg of brandy strapped around its neck, Laurel feigns exhaustion in order to obtain the rescue dog's emergency supply of liquor, on which he becomes hopelessly intoxicated. Indentured to work in the hotel kitchen an extra day for every dish they break, the boys find innumerable ways to add to their misfortune with one new dinnerware disaster after another until it seems that they will spend all of eternity in that kitchen. And there is the moment when Hardy serenades the object of his romantic affection with a rendition of the tender ballad "Let Me Call You Sweetheart", accompanied by Laurel on an oversize tuba, the incongruous booming tones of the instrument oddly complementing the pomp and splendor of Hardy's musical declarations of love.

There are also the delightfully surreal moments that exist free from the constraints of realistic narrative logic. At one moment, animated soap bubbles escape from a pipe organ that produce the notes of a song as they burst, and at another, a punctured gas pipe under the floor causes infernal flames to shoot forth wherever poor Oliver Hardy happens to be standing.

At one point, the boys find themselves trapped on a rickety wooden mountain bridge, perilously high across the Alps, with a piano and a gorilla -- a comic image for the ages. Ours is not to wonder how they got there, or what a gorilla is doing in the Swiss Alps. Laurel and Hardy approach any task with a kind of bullheaded determination and literal single-mindedness, which keep them in pursuit of achieving their goal even when logic or common sense would give anyone else pause for thought, and this is no exception. Suspended high above the gaping mountainous chasm, every twist and turn of the bridge -- swaying to and fro like some kind of insane fun-house attraction -- risks plunging them into the abyss.

Yet they view this predicament as they would any other and, despite the momentary terror of the situation, somehow all seems right in the world when Hardy, left by the oblivious Laurel to dangle from the collapsed bridge on the side of a mountain, gets knocked on the head by a falling rock, expressing mere annoyance at this latest inconvenience. Their universe has regained equilibrium, and they are on to their next misadventure, perhaps to attend Oxford, or join the Foreign Legion.

From the moment they appear, you find it impossible to take your eyes off of them. The boys' masterful comic interplay, which they make look so deceptively simple, astounds with its perfect rhythm and timing, every gesture, every glance and every pratfall performed with expert precision. Every facet of their screen characters is so thoroughly and richly defined to the point where they seem so real, so human that we feel like we are spending time with old friends when we see their films.

Numerous episodes stand out for their comic ingenuity. Spotting a Saint Bernard with a keg of brandy strapped around its neck, Laurel feigns exhaustion in order to obtain the rescue dog's emergency supply of liquor, on which he becomes hopelessly intoxicated. Indentured to work in the hotel kitchen an extra day for every dish they break, the boys find innumerable ways to add to their misfortune with one new dinnerware disaster after another until it seems that they will spend all of eternity in that kitchen. And there is the moment when Hardy serenades the object of his romantic affection with a rendition of the tender ballad "Let Me Call You Sweetheart", accompanied by Laurel on an oversize tuba, the incongruous booming tones of the instrument oddly complementing the pomp and splendor of Hardy's musical declarations of love.

There are also the delightfully surreal moments that exist free from the constraints of realistic narrative logic. At one moment, animated soap bubbles escape from a pipe organ that produce the notes of a song as they burst, and at another, a punctured gas pipe under the floor causes infernal flames to shoot forth wherever poor Oliver Hardy happens to be standing.